Vellum

In 2006, Irish archeologists pulled an ancient book out of a peat bog. Radiocarbon dating showed that the book was between 1,000 to 1,200 years old. Thanks to the low-oxygen conditions of the bog, the book was well enough preserved that the archeologists could tell it was a prayer book.

They could also tell that the book was made of soft calf-skin called vellum. This book, called the Faddan More Psalter, was proof that farmers contributed their animal products to create early literature.

The word vellum comes from an old French word for calf-skin, though vellum has also been made from sheep, goats, pigs, deer and even camels. To make vellum, a young animal is skinned and its soft hide is cleaned, bleached, stretched and scraped.

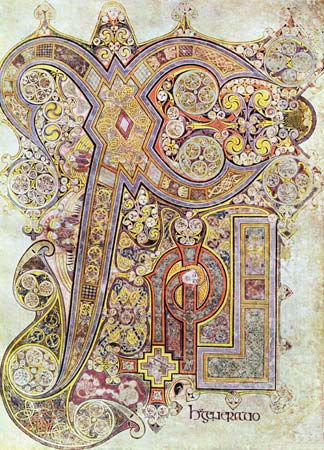

In Europe, vellum was popular from the days of the Romans until the medieval era. Early Christian texts, like the richly-illustrated Book of Kells, were hand-painted on vellum. Some early Buddhist texts were printed on vellum, and it was often used for Jewish Torah scrolls. Vellum was also used as canvas by artists like the late-medieval painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer.

A famous use of vellum was in the printing of the Gutenberg Bibles. One-fourth of Gutenberg’s famous Bibles were printed on vellum. Vellum was quite expensive, but nobles of the 1450s insisted on it. The 45 vellum copies of Bible required a total of 11,130 sheets of vellum—that was a huge contribution from animal agriculturalists.

Vellum is not as common today, but it still has uses in writing. Many Jewish Torahs are still printed on vellum, and tradition in England requires that each new British act of Parliament be printed on vellum.

The historic Book of Kells was written on animal skin. Photo from Encyclopedia Britannica